Mervyn F. Bendle

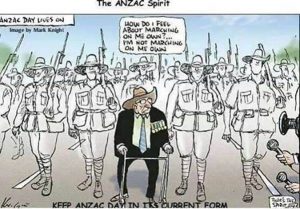

The war on the Anzac tradition is intensifying. A long-term foe, Professor Joan Beaumont of the Australian National University, has published Broken Nation: Australians in the Great War (2013) and she has been joined by an ex-army officer, James Brown, who has contributed Anzac’s Long Shadow: The Cost of Our National Obsession (2014) to the campaign of denigration of what is seen as a “festival of mythology” and “Anzackery”, as a review of Broken Nation on Guardian.com puts it. As such books and other recent works discussed below make clear, the attack on Anzac and the Digger legend is an elitist project explicitly dedicated to destroying the popular view of these traditions held by Australians, and is being led by a cadre of academics, media apparatchiks, and some disaffected ex-army officers overwhelmingly located in Canberra and ensconced in elite institutions, including the Australian Defence Force Academy, the Australian National University and the Australian War Memorial, where the Australian officer corps and bureaucratic elite receive their education.

According to Brown, “This year an Anzac orgy begins. A commemorative program that would make the pharaohs envious.” Speaking on the ABC’s 7.30 in February, Brown mangled the metaphor, complaining that “we’re about to embark on a four-year festival for the dead which in some cases looks like a military Halloween”. Claiming in his book to speak for soldiers who have served in Iraq and Afghanistan, Brown declares that they don’t want to be associated with the Anzac tradition: “They don’t want honour that rides with hubris. Or glory bestowed by a society that fetishises war but doesn’t know the first damn thing about fighting it.”

Is this really the perspective of contemporary Australian soldiers? Do they really see the upcoming centenaries as “an Anzac orgy”? Do they really lack all respect for Australian society and the Anzac tradition that seeks to honour the hundreds of thousands of their forebears who fought, died, or were maimed in the wars of the past century? If so, then the efforts of the anti-Anzac cadre operating in Australia’s elite institutions have been very effective indeed.

Or is Brown just projecting onto his comrades his own grievances, attitudes and values? Certainly he has a wide range of complaints to make about the military, particularly concerning authority and discipline. For example, he complains that troops wear gym clothes, thongs and T-shirts, listen to music, hit golf balls, stand around bonfires near combat zones, and aren’t sufficiently awestruck by their young officers. He quotes a report from a fellow “soldier-scholar” that complains the troops are spoilt and “feel entitled to be treated almost as Roman gladiators [expecting] everyone, including their superiors, to lavish them with attention”. Regrettably, according to Brown, “Australian officers are exceptionally careful not to be aloof from their soldiers”, and this has led to the loss of “valuable British officer traditions [that] delineate firmly between officer, warrant officer and soldier”. After all, “not all elitism is bad”. He laments that “discussing these deficiencies is difficult in a defence force trying to live up to the image of the exceptional Digger”, which is, of course, intrinsically anti-elitist and egalitarian.

Whatever the merits of Brown’s criticisms, it is deplorable that he blames the problems on the Anzac tradition and the Digger legend, which operate, in his view, as a sort of cultural cancer within the military, promoting mythical ideas about the capabilities of Australian soldiers, and giving them ideas above their station. Although he portrays himself as a critic of the military top brass, he is really providing them with an excuse for a systemic failure—blame Anzac and the Diggers. Similarly, if Australian army officers are incapable of dealing with their men, then Brown is also providing them with the excuse that it’s the corrosive effect of the Anzac and Digger traditions that’s the problem, not their own inadequacies.

Brown’s attitude towards Anzac echoes that of David Horner, Professor of Australian Defence History at the ANU. Forced to defend his summary dismissal of the military significance of Kokoda in 2012, Horner declared, “It’s all the Anzacs’ fault”, as the Daily Telegraph reported. “Everybody wants to be an Anzac. Everybody wants a medal. Everybody wants to be recognised … every child gets a prize. If you fought in a battle, it has to be a battle that was really important.” Horner was supported by Ashley Ekins, the Head of the Military History Section at the Australian War Memorial, who denounced the “excessive mythology about the Kokoda story”. The Japanese never intended to invade Australia, they insisted, so Kokoda had no strategic significance and its commemoration is an overblown indulgence by a people starved of real military glory. On the other hand, perhaps Australians could be forgiven for accepting the word of General Douglas MacArthur, the Supreme Commander, South West Pacific Area, when he declared in March 1945 that it had been Australia’s success in Papua that “turned the tide of battle on which all future success [had] hinged” and that Australia’s “brilliant” campaign helped “speed the Japanese defeat in New Guinea”, as the Sydney Morning Herald reported at the time.

Brown’s polemic echoes criticisms of the Anzac tradition made by the Left for some ninety years, since the ideal of the Anzac emerged during the Great War and easily swept aside the competing model of “Soviet Man” that the radical Left embraced in the aftermath of the Russian Revolution and wanted to impose on Australian workers after the takeover of local radicalism by the Communist International in the early 1920s. This failure has festered within the Left over the decades and it frequently unleashes a stream of invective that has reached a torrent at times, especially in the 1960s, when the current generation of senior historians began their Maoist “long march through the institutions” to positions of power from where they could mentor their radical successors, including any disgruntled ex-army officers who fancy an academic career and are prepared to toe the party line.

The general outlook of this cadre is exemplified not only by the books by Brown and Beaumont, and the exasperated utterances of Horner and Ekins, but by other recent iconoclastic attacks on the Anzac tradition and popular views of Australia’s military history. These include What’s Wrong With Anzac?: The Militarization of Australian History (2010), edited by Marilyn Lake and Henry Reynolds; Bad Characters: Sex, Crime, Mutiny and Murder and the Australian Imperial Force (2011), by Peter Stanley; and Zombie Myths of Australian Military History (2010) and Anzac’s Dirty Dozen (2012), both edited by Craig Stockings, like Brown an ex-army officer, and now a senior lecturer at the ADFA. I have previously discussed the anti-Anzac polemics contained in What’s Wrong With Anzac? (“Anzac in Ashes”, Quadrant, April 2010) so I will explore the other books here.

As these books reveal, many Australian military historians live in an elitist parallel universe, where they believe they alone possess the truth about the past, while all around them the ignorant masses indulge themselves pathetically in myths and fantasies about military glory. According to Zombie Myths and Anzac’s Dirty Dozen, such myths concern frontier wars, Breaker Morant, Gallipoli, the Western Front, the Anzac legend, the military prowess of the Diggers, their treatment of enemy combatants, the role of women in war, Kokoda, the threat of Japanese invasion, Vietnam, East Timor, and the central place of war in Australian history. In every one of these areas, the popular understanding of the events is allegedly wrong, nurtured by “bestselling popular histories not always based on archival research”, as Stockings complains in his introduction to Anzac’s Dirty Dozen. Tenured and comfortable in Canberra, these historians resent the popular success of allegedly inferior works produced by non-academic historians while their own purportedly more worthy efforts remain largely unread and without the recognition they feel they deserve. In a recent AWM Journal article, Beaumont called on her colleagues to “ensure scholarly studies reclaim the domain of popular history”.

Indeed, looking through the books credited to the contributors to Zombie Myths and Anzac’s Dirty Dozen, they are frequently notable only for their obscurity or unavailability. On the other hand, innumerable works of military history by authors like Les Carlyon, Paul Ham, Patrick Lindsay, Bob Wurth, Peter Thompson and Peter Fitzsimons are extremely popular and readily available.

Allegedly misled by such popular histories and denied the enlightenment provided by obscure military monographs, the masses and their leaders remain benighted. “The published and public spheres of Australian military history … are landscapes of legend [and] minefields of misconception”, according to Stockings in Anzac’s Dirty Dozen, and this goes for all “official publications, popular books and novels, the speeches of Anzac day and its associated political rhetoric, and the language of public commemoration”. All of these are “subordinated to a narrative bent on commemoration, veneration, and capturing the essence of idealised ‘Australian’ virtues”. This dismal view of the public presentation of the nation’s military history is supported by Stanley, who confesses in his chapter on “Monumental Mistakes: Is War the Most Important Thing in Australian History?” that he drafted speeches and talks for public figures extolling a version of Australia’s military past that he regards as untenable. Now, it seems, only historians like those represented in Stockings’s books possess the courage to “confront the persistent and general misconceptions of our military past, and to understand what really happened”, however destructive such alleged revelations might be for Australians’ view of their nation’s history.

In their deluded state, according to Stockings, Australians pathetically embrace a range of “zombie myths” about their country’s past military exploits, centred on “conceptions of national identity wrapped in the imagery of war, and the all-encompassing social implications of our central national legends—Anzac and the Digger”, as he laments in his introduction to Zombie Myths. These “monsters of the mind” have to be exposed to “the light of genuine and analytical scholarship”, as practised by his heroic historians, who alone can combat the zombies, armed like exorcists with “the holy water [of] reasoned arguments”, “the sharpened stakes [of] thorough analysis”, and “the crucifixes [of] critical rigour”.

As these images suggest, these military historians have embarked on an iconoclastic holy war against the Anzac tradition, an intellectual jihad against those historical narratives through which the Australian people seek to understand their nation’s history, sustain a sense of national identity, and redeem the promise of generations past never to forget those who sacrificed their lives on their nation’s behalf.

In his chapter on “Monumental Mistakes” Stanley pursues this jihad into the outer limits of absurdity, claiming that the nation’s efforts to commemorate those who sacrificed their lives in war should be matched by similar efforts to commemorate those who died in all sorts of other ways. “Arguably,” he insists, “more Australians have been touched by the trauma of car accidents killing loved ones, friends or neighbours than have been affected by deaths in war” and, he continues, the same applies to infant mortality, tuberculosis, mental diseases, cancer, natural disasters, drug abuse and suicide, all of which have taken more lives than war and should therefore be afforded at least the same recognition as the Anzacs. It is “peculiar at best and grotesque at worst” that Australia should memorialise “the sacrifice of its young countrymen at places like the Nek and Beersheba”, but ignore those who died in these other ways, he concludes.

At times Stanley appears to pull back from the threatening brink of utter absurdity, appearing to acknowledge that death in the service to one’s country occupies a different category from death through suicide or drug abuse, but he nevertheless returns obsessively to reiterate his central claim, insisting that the Anzac commemoration of fallen servicemen is unfair and contrived. According to him, it results not from society’s recognition of the intrinsic value of their sacrifice but is in fact “orchestrated by organised bodies such as ex-service organisations”, by government propaganda through the Department of Veterans’ Affairs, by the Australian War Memorial and by Anzac Day. “The Anzac ‘brand’ is being promoted” just like any other commodity, and exploited by politicians. The deaths it commemorates have no special place in the nation’s past and to think otherwise “is to skew our understanding of the experience of Australian history”. Moreover, this unfairly favours “old Anglo-Celtic families who [have] direct connections with those who served in and lived through the Great War”. The Anzac tradition is therefore an “essentially minority interest” that excludes “non-Anglo-Celtic Australians”. Stanley concludes with the hope that “the critical approach to military history”, that he claims to practise will prevent “the myth” from being “entrenched” for the 1915 centenary of the Anzac landings in Gallipoli.

To achieve this aim, Stanley and his comrades have set up the “Honest History” website (named without any apparent intention of irony). This was devised after they failed to get funding to make “a television program questioning the role of the Anzac tradition in our history”, as the website explains. Although they were unsuccessful, “the group looked for other opportunities. The impending centenary of World War I, particularly the centenary of the landing at Gallipoli, was an obvious trigger”, and so they established “Honest History”, whose board members and supporters include leading critics of Anzac.

The website recently provided a convenient platform for Stanley to defend a controversial but entirely predictable feature on Gallipoli run several times on ABC television. This was based on Stanley’s book Bad Characters: Sex, Crime, Mutiny and Murder and the Australian Imperial Force (2011). By ransacking various archives and other collections, Stanley compiled a range of stories about Australian soldiers being insubordinate and disobedient, shirking, malingering, deliberately injuring themselves, and contracting venereal diseases, as well as committing serious criminal acts including desertion, mutiny, rape and murder. Unsurprisingly, the book’s prurience and negativity made it the joint winner of the Prime Minister’s Prize for Australian history in 2011, awarded by a committee chaired by the communist historian and chief author of the notorious national history curriculum, Professor Stuart Macintyre of the University of Melbourne. The feature’s broadcast on January 27, 2014, provoked the Liberal member for Bass, Andrew Nikolic, a former brigadier, to question the propriety, as the centenary approaches, of the ABC giving “prominence to those claiming that the story of Gallipoli is a ‘myth blown out of all proportion’ [and that] we should focus on the misogyny, racism, discrimination and exploitation at Gallipoli [and] honour the opinions of those who trawl through the history of 1915 Cairo brothels”.

Stanley is also happy to unburden Australians about the threat of Japanese invasion during the Second World War. In his chapter in Zombie Myths, “Dramatic Myth and Dull Truth”, he claims this is a myth fed on unfounded fears and fostered by the state. “The Australian Government actually and actively fostered alarm. Its information and propaganda campaigns fuelled the conviction that Japan’s forces” were heading for Australia, and this myth was subsequently resurrected by those politicians and others promoting “the novel but quite spurious notion that a ‘Battle for Australia’ was fought in 1942”. This was augmented by “misleading folk beliefs or hoaxes” associated with troops who served in New Guinea, along with “superficial” histories like 1942: Australia’s Greatest Peril (2008) by Bob Wurth, with whom Stanley has been losing a running battle. According to Stanley, “the question of an invasion of Australia [was] so peripheral to the history of the war in the South-West Pacific that it was relegated to footnotes” in mainstream histories.

This is familiar ground for Stanley, who, as Principal Historian at the Australian War Memorial, had gained attention in 2002 with an article, “He’s (Not) Coming South—the Invasion That Wasn’t”. With barely concealed contempt, Stanley denounced “Australia’s self-centred approach to the war”, insisted that the threat of Japanese invasion “did not exist, was known not to exist and [had] been exaggerated”, and declared that “it is time that Australians stopped kidding themselves that their country faced an actual invasion threat and looked seriously at their role in the Allied war effort” to acknowledge its marginal significance. In a subsequent article, “Threat Made Manifest” (2005), Stanley (who was born in Britain) lamented how “Australians want to believe that they were part of a war, that the war came close; that it mattered … Set against the prosaic reality, the desire is poignant and rather pathetic.”

Perhaps it is best to leave Stanley there, turning to the other historians and leaving him to enjoy his recent appointment as a professor at the Australian Defence Force Academy, where he can shape the thinking of future generations of officers in the defence forces.

Another zombie myth that this cadre of historians feel obliged to demolish concerns the legendary August 1915 offensive at Gallipoli. As Rhys Crawley notes in his chapter in Zombie Myths, “The Myths of August at Gallipoli”, the Australian and New Zealand memorials at Lone Pine and Chunuk Bair not only “mark the most significant gains made by Anzac troops”, during the action, but are sanctified “places of mourning”. Nevertheless, he feels compelled to debunk the basis for their consecration, insisting that they “embody an interpretation of Gallipoli that is much closer to historical fiction than historical fact”, and is “without doubt, a fairytale”. “In truth, August at Gallipoli is most accurately described as an irrefutable and utter disaster.” Once again, what even Crawley recognised as fundamental “symbols of national sacrifice and national identity” are deconstructed and shown to have no foundation. His endeavours in this area were rewarded with a PhD and a postdoctoral fellowship at the Australian National University.

It’s a characteristic of many contributions to Zombie Myths and Anzac’s Dirty Dozen that they seldom cite in any detail or even identify the proponents of the myths that they are attacking. Consequently, while efforts like Crawley’s purport to be standing out against a tide of ignorance or misrepresentation, in fact the mainstream view of the actions concerned is not dissimilar to the one he offers. Certainly, the assessment of the August 1915 campaign offered in The Oxford Companion to Australian Military History is consistent with Crawley’s, so who is it he is arguing with? And is his iconoclastic attack on the commemorative significance of Lone Pine really necessary?

According to Stockings, the entrenched enemy that he and his elitist comrades are so heroically challenging is “the average Australian”. As he complains in “There Is an Idea That the Australian is a Born Soldier”, in Zombie Myths, this species “has a general impression—a vague feeling—that not only have Australian troops acquitted themselves well in past conflict, they are, at some level ‘natural’ soldiers … naturally superior to their adversaries … They were, after all, the heirs of Anzac”, indulging in a racist, sexist and homicidal “legend of idealised Australian masculinity—the quintessential male—with all the necessary warrior attributes attached” and able to “kill and kill well”. Using the Libyan campaign of 1940–41 as a case study, he acknowledges that the Australian assault on Bardia resulted in 40,000 Italian soldiers being taken prisoner at a cost of only 456 Australian casualties, while the attack on Tobruk netted another 26,000 prisoners. Nevertheless, he sees these battles not in terms of concrete military outcomes but in terms of how they were represented in the media, accepting Robin Gerster’s insistence in Big-Noting; The Heroic Theme in Australian War Writing (1992), that the Anzac legend is all about men “big-noting” themselves. He also accepts Gerster’s view that popular writers have become mere “publicity agents for the ‘Digger’, as an exemplar of heroic racial characteristics”.

Stockings takes particular exception to the descriptions provided by outstanding war correspondents like Chester Wilmot and Alan Moorehead, amongst others, which he feels over-emphasised the courage of the Anzacs and inappropriately exhibited “a strange fascination” with the rugged musculature of “these men from the dockside of Sydney and the sheep stations of the Riverina”, as Moorehead put it in what Stockings rejects as a mere “caricature”. He simply rejects the commonsense conclusion that these men actually might have been physically tough, strong, brave, and superior fighters, insisting that such suggestions of superiority over the Italians are “ethnic slurs”, and merely expressions of the Anzac myth—the “stereotyped Australian identity”, without any basis in reality. He similarly rejects any suggestion that any particular “fighting spirit” was demonstrated by the Australians or that they were motivated by any “spirit of Anzac”. In the end, “Anzac is a social construct”, and it all came down to the tactical incompetence of the Italians and the comparatively superior training of the Australians. Apparently the 66,000 Italian prisoners virtually captured themselves.

John Connor, also of the Australian Defence Force Academy, makes similar claims in Anzac’s Dirty Dozen when debunking the alleged myth of “The ‘Superior’, All-Volunteer AIF”: any military success enjoyed by Australian troops reflects no particular qualities associated with the Anzac myth that they might possess, such as mateship, bravery, physical fitness or initiative, but only their training, weaponry and leadership. He closely aligns himself with Elizabeth Greenhalgh, also at the Australian Defence Force Academy, who in Zombie Myths seeks to debunk the view that “Australians broke the Hindenburg Line”. Like Stockings, Connor and the rest of this cadre, she regards the Anzac tradition as racist, sexist and nationalist mythology.

This antipathy pervades Joan Beaumont’s Broken Nation, a major foray by the anti-Anzac academic elite. It offers a chronological account of the First World War, a discussion of social and political events on the home front, and invokes the tragic loss of young lives, while repeatedly dismissing Anzac and the Diggers. It has been welcomed by other cadre members, including Stanley, who, in his review for the Sydney Morning Herald on November 30 last year expressed particularly pleasure that it wasn’t written “by a journalist ’storian [sic] waving the Aussie flag, bragging about Diggers and damning pommy generals”. He lauds Beaumont’s style and remarks oddly that this was “because she’s spent years trying to get undergraduates to look up from their iPhones”, which appears to reflect poorly on her capacity to engage her students. If this is the case, then it may reflect the iconoclasm and bleakness of her vision and determination to leave no element of the Anzac legend intact.

Anzac is referred to some 400 times in Beaumont’s book. When they are not just descriptive these references are invariably condemnatory, dismissive, or highly qualified, with continual references to the Anzac “legend” or “myth” and to the “digger”, to indicate that the terms refer to things without actual substance or of dubious reality. For example, she claims that, even though “the Anzac ‘legend’ would gain a firm hold on the cultural imagination of the Australia media and public [it] overstated the performance and uniqueness of the Australian ‘digger’”. Anzac is “a narrative of hyperbole”, which falsely claims that “Australian men [were] exceptional fighters … made a decisive contribution to Allied victory and had performed exceptional feats in war … manifested qualities and solidarity in battle [and proved] themselves worthy of the Anglo-Saxon race and their forebears who had conquered the Australian bush”. It illegitimately became “the dominant narrative of the war … performing the ‘mythic’ function [of] justifying later institutions”, and is therefore “invoked not just by politicians, but by sportsmen, policemen, and others who champion the values of the collective and team over the individual”. (This seems a bit rich coming from a senior member of the Australian historians’ guild where groupthink is a required characteristic.) The concept of mateship is similarly brushed aside, so that when Beaumont quotes Charles Bean describing how the Anzacs were determined at all times to stand by their mates, she insists that this is no “particular Australian virtue”, but is just an “informal source of discipline” found in all armies. The book’s reviewer for Guardian.com found this debunking of mateship particularly gratifying.

Instead of Anzac, Beaumont insists that the home front and especially Australian women must be central to any history of the war. In her view, “it was the Australian population on the home front … who underpinned the national war effort [and] accepted casualties on a scale that would be unthinkable today”. The war was an ordeal that took a terrible toll on non-combatants, and their heroism, especially that of women, has been unfairly ignored. After all, she points out, military censorship of letters from the front was lax, and while the men at the front may actually have endured misery, fear, discomfort, despair, cynicism, violence, mutilation, disfigurement and death, the women at home had to read about it.

This approach recalls the chapter by Eleanor Hancock (also of the Australian Defence Force Academy) in Dirty Dozen, “‘They Also Served’: Exaggerating Women’s Role in Australia’s Wars”. Although scathing in her disdain for the “Anglo-Celtic … Anzac mythology [and] military fable”, Hancock also acknowledges that the misguided enthusiasm of radical feminists to have women share the Anzac glory has resulted in some absurd claims being made by historians, safe in the knowledge that any criticism they attract will be dismissed “as a sexist form of gate-keeping”. Desperate to “shift the focus to, or heighten the attention given to, women’s own experiences” such historians have responded “by artificially extending Anzac to encompass women by exaggerating, wherever possible, their role and contributions to Australia’s twentieth-century wars”.

Nevertheless, Beaumont is an affirmative-action historian, insisting that women bore an intolerable burden imposed by the war and that this contributed to a general demoralisation on the home front, with Australians rejecting the call by political and military leaders to support the troops overseas, causing recruitment to decline precipitously in the later years of the war. So serious did this become, she insists, that “had the war continued into 1919, the Australian narrative might not have ended in triumphalism, but rather in retrenchment and decline—and perhaps even rebellion”. She concludes, incredibly, that Australia might have gone down the German path, with the army and society disintegrating, and “there might even have been an Australian version of the ‘stab in the back’ theory that so infected German political life after the war”, perhaps seeing an Australian version of Nazism emerge in conjunction with the Anzac tradition, the Secret Army, and “the Old and New Guard in New South Wales and the White Army in Victoria”, which were “mobilised against the ‘threat’ from the left” and carried out “vigilante-style attacks against meetings of radicals”. Ultimately, the Anzac legend reflected a “post-war Australia [that] was polarised and dominated by the forces of conservatism and reaction”.

This near-apocalyptic vision leads Beaumont to depict Australia as a “broken nation” at the end of the war, riven with paranoia, extremism and division. For her, it was a world polarised between volunteers and shirkers, conscriptionists and anti-conscriptionists, Protestants and Catholics, workers and bosses, radicals and reactionaries. “The insults, calumny and accusations … of the war years were not forgotten and continued to poison public life for many years”, leaving Australia “less tolerant of difference, more fearful of radicalism, and more xenophobic”. Remarkably, Beaumont sees the Anzac tradition as both a cause and product of this malaise rather than as an attempt to find an ethic of integration that might have helped resolve it. She also discounts as mere xenophobia the widespread hatred of the communists, as if they were not the local representatives of a country that had pulled out of the war at a critical time in 1917, allowing hundreds of thousands of German troops to be transferred to the Western Front to overwhelm the allies, and who, moreover, were acting upon the directions of a foreign country in calling for violent revolution in Australia.

Predictably, Beaumont sees the eclipse of the ALP—“a reforming party of national government”—and the dominance of non-Labor parties as one of the most “negative legacies” of the war. She also claims that the Anzac legend has unfairly obscured the memory of the 1917 general strike, which she seems to see as a refutation of the Anzac ideal, and tellingly cites Green Left Weekly as a source for her views. She also endorses Marilyn Lake’s claim in What’s Wrong With Anzac? that the Anzac legend “worked to sideline different stories of nation-building, oriented not to military prowess, but to visions of social justice and democratic equality”. She writes as if these were values foreign to the Anzacs, and that benefits would have flowed from the ideological victory in the postwar period of the Communist Party of Australia, which was completely beholden to the dictates of the Communist International that systematically betrayed the workers of the world for decades.

Ultimately, Beaumont is dumbfounded by Anzac. As she points out, at the time of her student days “it seemed that the dominance of the Anzac ‘legend’ was being eroded [by] feminism, student activism”, and the anti-war movement, which debunked it as “militaristic, misogynistic, and anachronistic”. It was expected to “wither away”, but instead it underwent a powerful resurgence driven by popular sentiment in a manner she professes not to understand.

Indeed, Broken Nation reflects the bankruptcy of academic Australian history, which is so ideologically aligned with the progressivist narrative centred on the Labor Party and the social movements and fashionable causes of the Left, that it is uncomprehending, dismissive and often openly hostile to forces that are not so aligned. The Anzac legend is an intellectual and ideological challenge for these historians that they cannot cope with and they find it galling that it receives the attention it does. Consequently, they are now seeking to destroy the Anzac legend on the occasion of its centenary.

Nearly a century ago Australians pledged, “Lest we forget”. They should now be allowed to honour this centenary without constant sniping from an anti-Anzac elite of obsessive academic leftists and disgruntled ex-officers.

Among his articles for Quadrant, Mervyn F. Bendle has written “How Paul Keating Betrayed the Anzacs, and Why”, January-February 2014; “Anzac in Ashes”, April 2010; “The Intellectual Assault on Anzac”, July-August 2009; and “Gallipoli: Second Front in the History Wars”, June 2009.

Speak Your Mind