Date

February 25, 2013

David Forbes

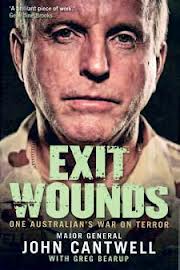

Major-General John Cantwell has told a parliamentary inquiry the Defence Force needs to continue its efforts to de-stigmatise mental health problems if it is to deal with the growing number of veterans returning from operations with post traumatic stress disorder. Soldiers will not acknowledge they have PTSD until the ADF ”normalises” mental health problems and treats them in the same way it does physical injuries.

Major-General John Cantwell has told a parliamentary inquiry the Defence Force needs to continue its efforts to de-stigmatise mental health problems if it is to deal with the growing number of veterans returning from operations with post traumatic stress disorder. Soldiers will not acknowledge they have PTSD until the ADF ”normalises” mental health problems and treats them in the same way it does physical injuries.

He should know. From January 2010 to January 2011, he was the National Commander of Australian Defence Forces in Afghanistan. He’s spoken and written openly and honestly about his own post-traumatic stress and depression.

We speak often of the mental casualties of war, the soldiers who suffer from PTSD, depression and alcohol abuse and the families that can break down because of these problems. Yet for someone so senior to speak so openly and eloquently is extraordinary.

It is clear Major-General Cantwell is a leader not just in battle. By speaking about having had mental health problems, he is signalling to all those soldiers, sailors and airmen and women that acknowledging you have problems coming to terms with the horrors of war is OK. In fact, for those suffering, it is the first vital step in getting back to good health. iframe>

As illustrated in the Canadian defence forces, when Major-General Romeo Dallaire openly acknowledged his PTSD after serving in Rwanda, such pronouncements can result in profound shifts in awareness and understanding of mental health problems within the organisation.

Overseas estimates on the prevalence of mental health problems in defence personnel returning from Iraq and Afghanistan vary considerably, from about 20 per cent in the US to less than 10 per cent in Britain.

While rates of mental health problems for Australian troops returning from the Middle East are being researched at present, the landmark defence mental health prevalence study published in 2011 demonstrated that about 20 per cent of serving members were experiencing mental health problems, with 8 per cent reporting PTSD.

In the past 10 years, defence forces around the world have made great improvements in acknowledging the potential mental health impact of military service and in actively addressing the issues. Many defence forces have initiated programs to bolster psychological resilience before deployment. Support is provided for returning troops and their families, along with improved early detection of problems and better access to high quality mental healthcare.

While Australia has done very well in this area, ranking along with the best in the world, there is more that needs to be done.

Several key points should be remembered as we prepare for the return of defence personnel from some of the most difficult war zones in which we have been involved.

First, the majority, while they may experience readjustment difficulties, are unlikely to develop diagnosable mental health disorders. This demonstrates the value of personal coping strategies and the support of their units, commanders, family and friends in potentially providing important protection from the development of mental health disorder.

Secondly, while the system we have in place to support those who do develop mental health problems still needs work, effective treatments and programs of support are readily available. This is a far cry from the 1970s, when our Vietnam veterans were left to integrate back into civilian life with little in the way of emotional, social or psychological support.

Major-General Cantwell is right, however. It is built, as he says, into the psyche of the warrior to hide problems, particularly psychological ones. In addition, fears for the impact on their military careers of reporting these problems further fuels this reluctance.

Important challenges lie ahead for defence forces around the world in preventing or reducing the psychological effects of military conflict.

We now have the research data and intervention programs to help us identify and assist those who need help readjusting after their military experiences.

Defence Force personnel suffering from the effects of PTSD or other mental health problems should know they are not alone and help is available. They must be supported by their commanders and colleagues, however, and have the personal strength and courage to seek that help.

Professor David Forbes is the director of the Australian centre for post-traumatic mental health in the department of psychiatry at the University of Melbourne

Speak Your Mind